RESIDENCIA No. 12

ESCILA / MAL MENOR, MAL HECHO

Niels Bugge

Descarga el catálogo / Download Catalog ︎

Este título hace alusión al pasaje odiséico donde el héroe que regresa a casa, debe guiar a su barco y con él a toda su tripulación, a través de un estrecho marítimo flanqueado en uno de sus lados por un inconmensurable monstruo llamado Caribdis; y en el opuesto, por un monstruo de seis cabezas llamado Escila. El texto homérico nos hace entender que el héroe, frente a la inminencia, evalúa que navegar por el lado de Escila que devorará al menos a seis de sus tripulantes, es una mejor decisión que enfrentarse a Caribdis, quien sin duda tragaría el barco en su totalidad.

Así “entre Escila y Caribdis” se ha convertido en una alegoría de tener que elegir entre dos males, y Escila, por extensión, ha llegado a simbolizar "el mal menor".

Niels Bugge, se ha sentido atraído por este concepto, asociándolo a las narrativas neoliberales de escasez y urgencia, donde la elaboración de estrategias y la supuesta toma de buenas decisiones, descartan en gran medida perspectivas más amplias y fundamentales.

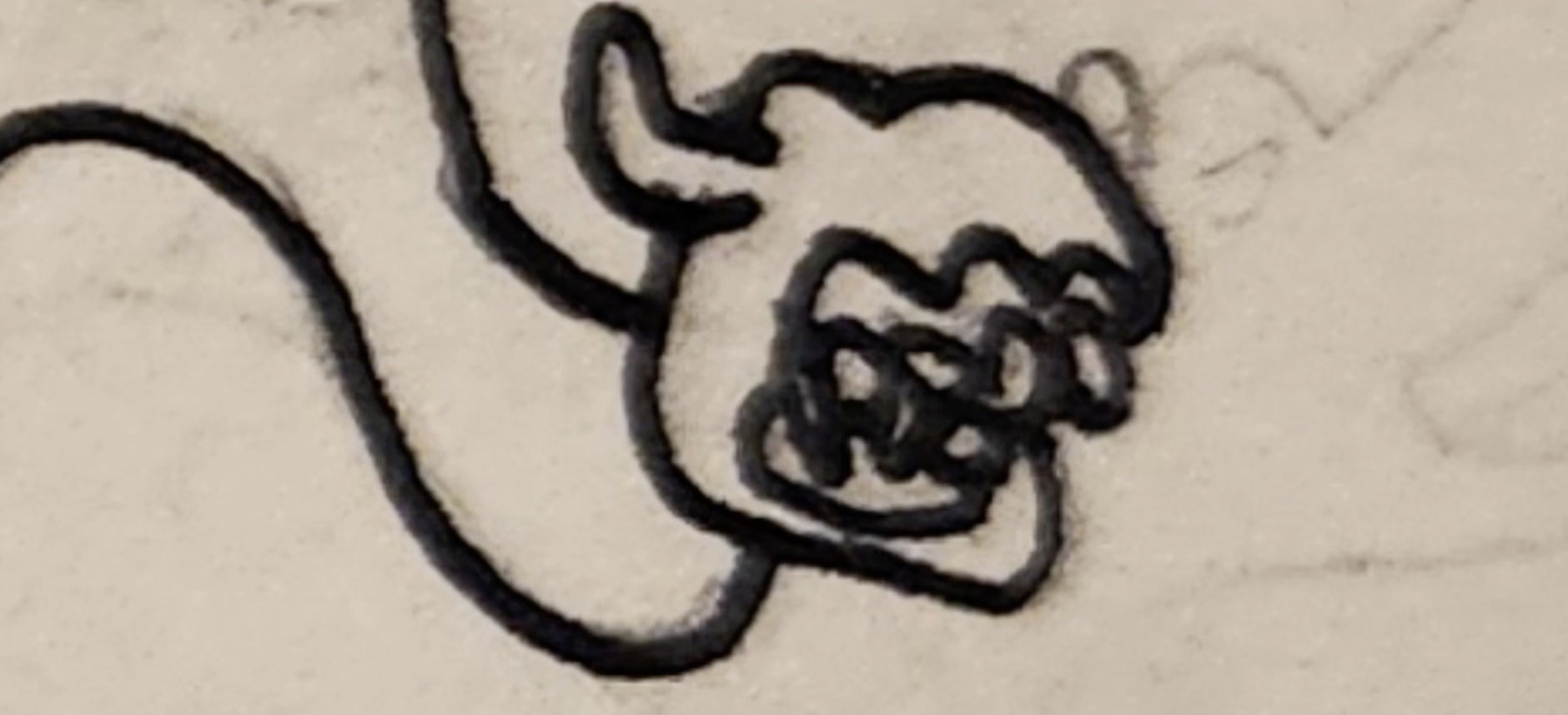

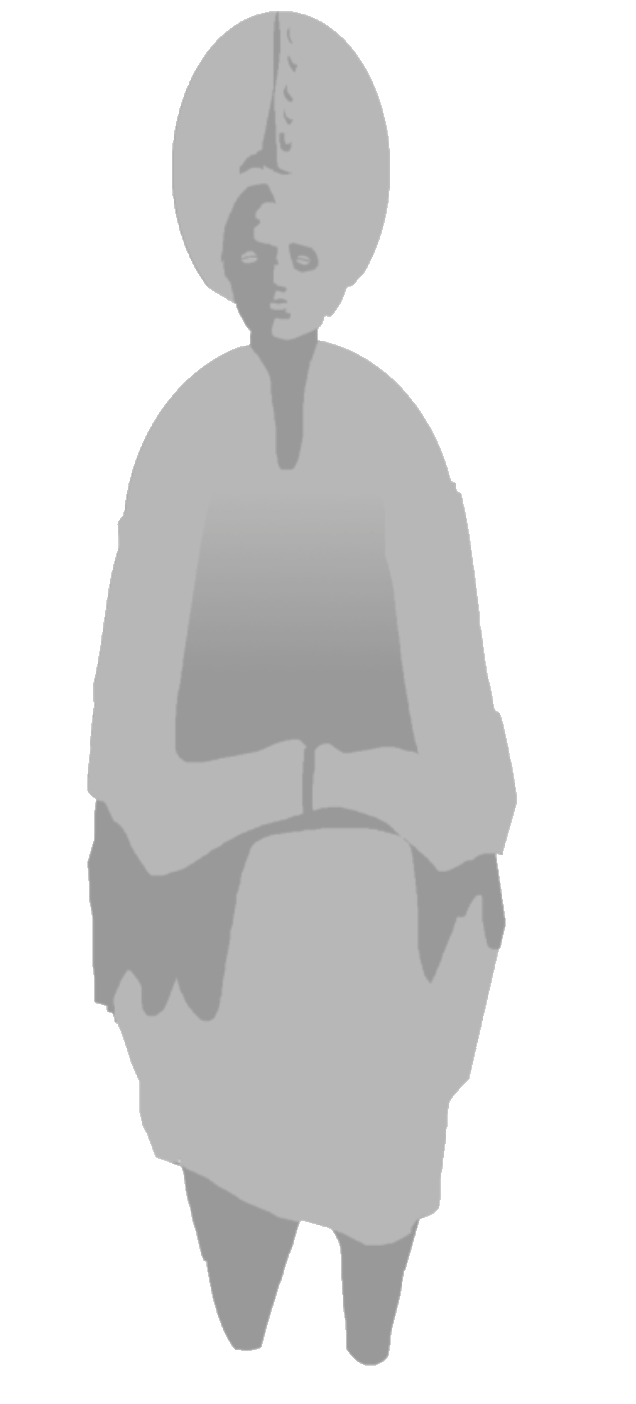

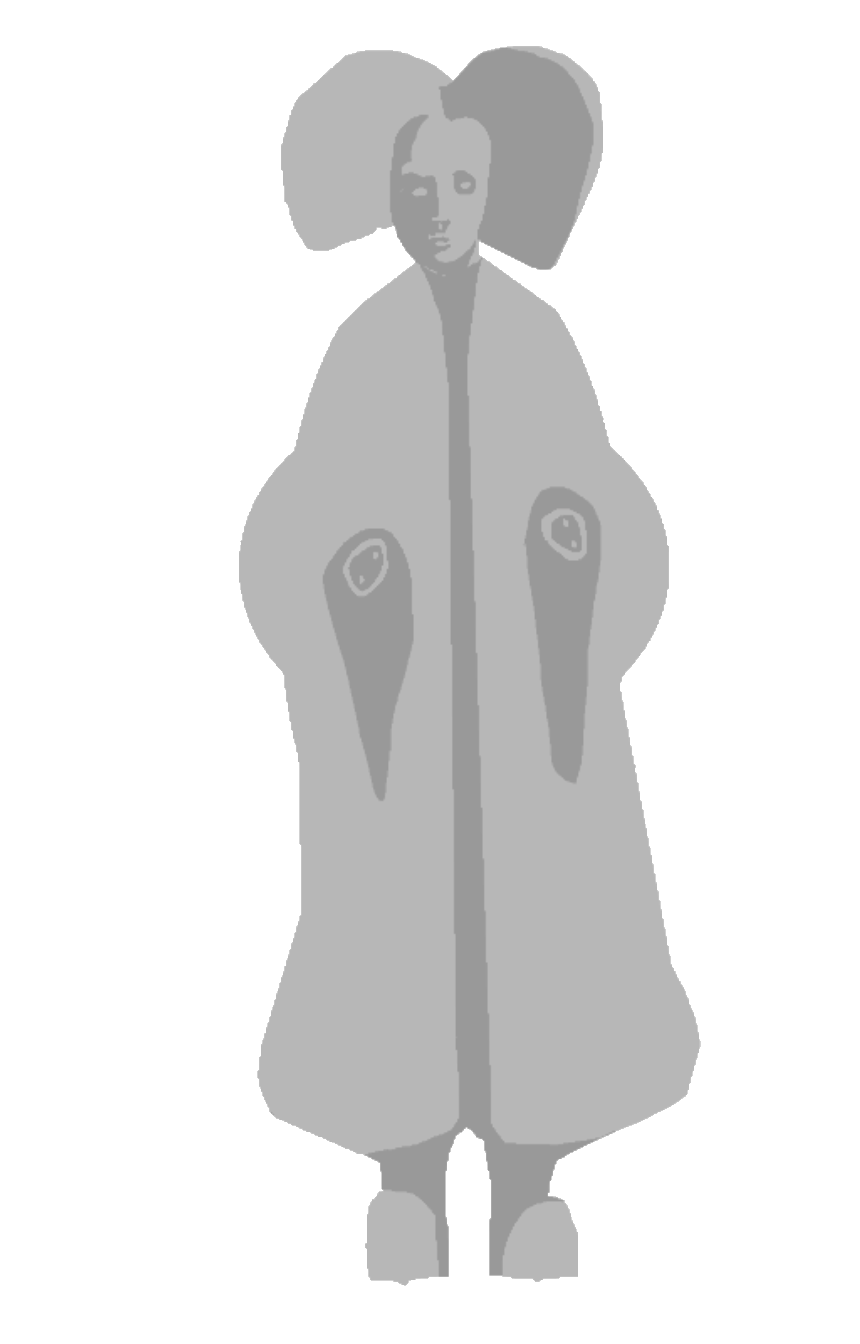

A pesar de su posición destacada en la historia (probablemente) más conocida de la antigüedad europea, Escila está en gran medida ausente del legado visual de la mitología griega, lo cual es inusual, considerando el impacto de sus contrapartes más conocidas, como Medusa, el Minotauro, la Hidra, Pegaso, la Esfinge o Cerbero. En la Odisea, se describe a Escila con doce piernas descoyuntadas, como tentáculos, con seis cabezas monstruosas sobre cuellos serpentinos. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las representaciones antiguas de ella se apartan del texto de Homero, representándola más bien como una sirena con las cabezas de seis perros que sobresalen de su abdomen.

Así “entre Escila y Caribdis” se ha convertido en una alegoría de tener que elegir entre dos males, y Escila, por extensión, ha llegado a simbolizar "el mal menor".

Niels Bugge, se ha sentido atraído por este concepto, asociándolo a las narrativas neoliberales de escasez y urgencia, donde la elaboración de estrategias y la supuesta toma de buenas decisiones, descartan en gran medida perspectivas más amplias y fundamentales.

A pesar de su posición destacada en la historia (probablemente) más conocida de la antigüedad europea, Escila está en gran medida ausente del legado visual de la mitología griega, lo cual es inusual, considerando el impacto de sus contrapartes más conocidas, como Medusa, el Minotauro, la Hidra, Pegaso, la Esfinge o Cerbero. En la Odisea, se describe a Escila con doce piernas descoyuntadas, como tentáculos, con seis cabezas monstruosas sobre cuellos serpentinos. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las representaciones antiguas de ella se apartan del texto de Homero, representándola más bien como una sirena con las cabezas de seis perros que sobresalen de su abdomen.

E sta disyunción, que ya se daba en la antigüedad, apunta hacia una posible razón para la ausencia comparativa de Escila. Tal vez Escila no logra atraer la imaginación de la misma manera que, por ejemplo, Medusa, Quetzalcóatl o el Xenomorfo, porque su diseño es deficiente; y simplemente no logra activar un proceso interno de creación de imágenes.

Pero irónicamente, quizá estos defectos en su descripción-diseño, puedan ser apropiados para un monstruo que representa "el mal menor", en una falsa dicotomía.

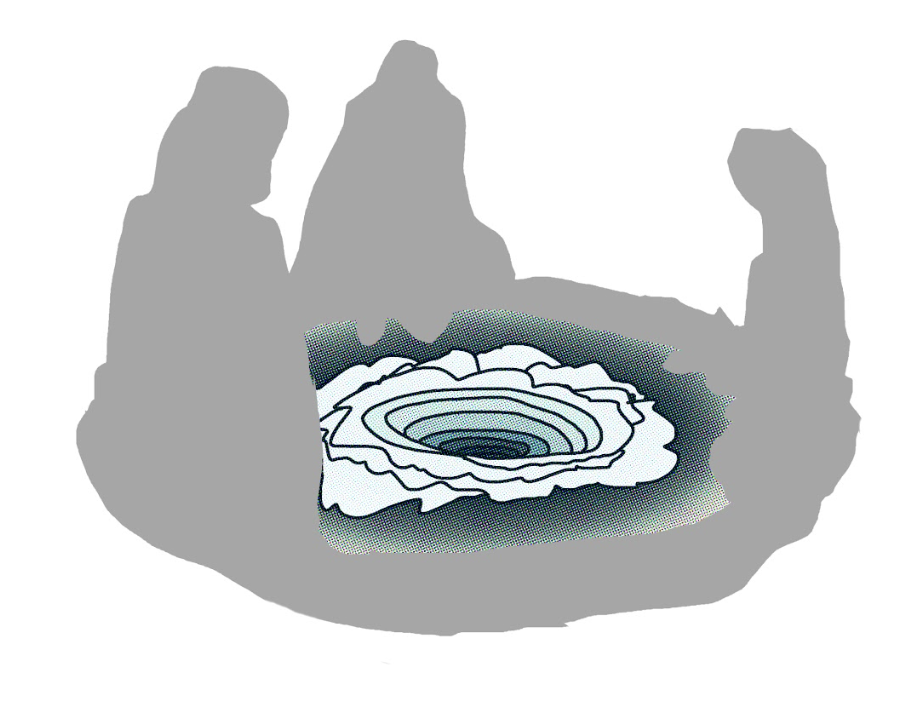

Sin embargo, para Niels, estas consideraciones no son fines en sí mismas. Son motores que impulsan un proceso creativo, que se centra en la experimentación con la forma y la composición, en el modelado 3D y sus transiciones hacia la impresión y la escultura. Estas transiciones se abordan como movimientos opuestos: para las esculturas, yendo desde la superficie plana de la pantalla, al mundo físico del volumen. Este movimiento se invierte en el proceso de impresión: donde el mundo móvil de luces ajustables, texturas dinámicas y formas instantáneamente maleables se congela y se transfigura en la planitud gráfica de la serigrafía.

Sin embargo, estos movimientos no son ni reductivos ni acumulativos, son espacios o fallos que incitan a decisiones intuitivas y abren nuevos caminos, por ejemplo, cuando una serigrafía no puede representar el brillo de un detalle de metal, o cuando las cavidades de una escultura a punto de ser fundida exigen un diseño que se aparte de sus orígenes digitales.

A través de estas transiciones técnicas, las obras de Niels navegan entre una gama de temas, que van desde el fracaso de la imaginación y la disonancia cognitiva hasta la fascinación por la violencia, los monstruos y el contexto geopolítico, en el que esta reflexión creativa, llamada Escila, se desarrolla.

Pero irónicamente, quizá estos defectos en su descripción-diseño, puedan ser apropiados para un monstruo que representa "el mal menor", en una falsa dicotomía.

Sin embargo, para Niels, estas consideraciones no son fines en sí mismas. Son motores que impulsan un proceso creativo, que se centra en la experimentación con la forma y la composición, en el modelado 3D y sus transiciones hacia la impresión y la escultura. Estas transiciones se abordan como movimientos opuestos: para las esculturas, yendo desde la superficie plana de la pantalla, al mundo físico del volumen. Este movimiento se invierte en el proceso de impresión: donde el mundo móvil de luces ajustables, texturas dinámicas y formas instantáneamente maleables se congela y se transfigura en la planitud gráfica de la serigrafía.

Sin embargo, estos movimientos no son ni reductivos ni acumulativos, son espacios o fallos que incitan a decisiones intuitivas y abren nuevos caminos, por ejemplo, cuando una serigrafía no puede representar el brillo de un detalle de metal, o cuando las cavidades de una escultura a punto de ser fundida exigen un diseño que se aparte de sus orígenes digitales.

A través de estas transiciones técnicas, las obras de Niels navegan entre una gama de temas, que van desde el fracaso de la imaginación y la disonancia cognitiva hasta la fascinación por la violencia, los monstruos y el contexto geopolítico, en el que esta reflexión creativa, llamada Escila, se desarrolla.

NB, OCSN / CDMX, 2024

This title alludes to the passage in the Odyssey where the hero, returning home, must guide his ship and his entire crew through a narrow strait flanked on one side by an immeasurable monster called Charybdis; and by a six-headed monster called Scylla on the other. The Homeric text makes us understand that the hero, knowing that a monster will attack his ship anyway, evaluates that sailing on the side of Scylla which will devour at least six of its crew members, is a better decision than facing Charybdis which would swallow the ship in its entirety.

Thus “between Scylla and Charybdis” has become an allegory of having to choose between two evils, and Scylla, by extension, has come to symbolize the lesser evil.

Niels Bugge has been attracted to this concept of the lesser evil, associating it with neoliberal narratives of scarcity and urgency of present and recent past. These narratives which underlie the development of strategies and the supposed making of good decisions, largely discard broader and more fundamental perspectives.

Despite her prominent position in (probably) the best-known story of European antiquity, Scylla is largely absent from the visual legacy of Greek mythology. Which is unusual, considering the impact of her better-known counterparts such as Medusa, Minotaur, Hydra, Pegasus, the Sphinx, or Cerberus. Scylla in the Odyssey is described as having twelve disjointed, tentacle-like legs, with six monstrous heads on serpentine necks. However, most ancient portrayals of her depart from Homer’s text, depicting her rather as a mermaid with the heads of six dogs protruding from her midriff.

Thus “between Scylla and Charybdis” has become an allegory of having to choose between two evils, and Scylla, by extension, has come to symbolize the lesser evil.

Niels Bugge has been attracted to this concept of the lesser evil, associating it with neoliberal narratives of scarcity and urgency of present and recent past. These narratives which underlie the development of strategies and the supposed making of good decisions, largely discard broader and more fundamental perspectives.

Despite her prominent position in (probably) the best-known story of European antiquity, Scylla is largely absent from the visual legacy of Greek mythology. Which is unusual, considering the impact of her better-known counterparts such as Medusa, Minotaur, Hydra, Pegasus, the Sphinx, or Cerberus. Scylla in the Odyssey is described as having twelve disjointed, tentacle-like legs, with six monstrous heads on serpentine necks. However, most ancient portrayals of her depart from Homer’s text, depicting her rather as a mermaid with the heads of six dogs protruding from her midriff.

This disjunction, already occurring in antiquity, hints towards a possible reason for Scylla's comparative absence. Maybe Scylla fails to attract the imagination in the same way as for example medusa, or Quetzalcoatl or the Xenomorph, because her design is bad; it simply fails to activate an internal image making process.

Ironically, the defects in her design-description might be appropriate for a monster representing "the lesser evil" in a false dichotomy.

However, for Niels, these considerations are not ends in themselves. They are motors that drive a creative process, which focuses on experimentation with form and composition, on 3D modeling and its transitions to printing and sculpture. These transitions are approached as opposite movements: for sculptures, going from the flat surface of the screen, to the physical world of volume. This movement is reversed in the printing process: where the mobile world of adjustable lights, dynamic textures and instantly malleable shapes is frozen and transfigured into the graphic flatness of the screen print.

These movements are neither reductive nor cumulative, they are gaps or failures that prompt intuitive decisions and open new paths. For example when a screen print cannot represent the shine of a metal detail, or when the gaps in a sculpture about to be cast demand departures from its digital model origins.

Through these technical transformations, Niels’ works travel between a range of themes, from failure of imagination and cognitive dissonances, to the fascination with violence, monsters, and the geopolitical context in which this creative reflection, called Scylla, unfolds.

NB, OCSN / CDMX, 2024

Ironically, the defects in her design-description might be appropriate for a monster representing "the lesser evil" in a false dichotomy.

However, for Niels, these considerations are not ends in themselves. They are motors that drive a creative process, which focuses on experimentation with form and composition, on 3D modeling and its transitions to printing and sculpture. These transitions are approached as opposite movements: for sculptures, going from the flat surface of the screen, to the physical world of volume. This movement is reversed in the printing process: where the mobile world of adjustable lights, dynamic textures and instantly malleable shapes is frozen and transfigured into the graphic flatness of the screen print.

These movements are neither reductive nor cumulative, they are gaps or failures that prompt intuitive decisions and open new paths. For example when a screen print cannot represent the shine of a metal detail, or when the gaps in a sculpture about to be cast demand departures from its digital model origins.

Through these technical transformations, Niels’ works travel between a range of themes, from failure of imagination and cognitive dissonances, to the fascination with violence, monsters, and the geopolitical context in which this creative reflection, called Scylla, unfolds.

NB, OCSN / CDMX, 2024

Niels Henrik Bugge_Artist CV_English